Asset Liability Management Strategies for Non-Complex and Complex Credit Unions [White Paper]

Key Takeaway

As credit unions look to expand, implementing sound ALM strategies will allow the protection of earnings and capital amidst a volatile rate environment.

How Can We Help You?

Founded in 2003, Wilary Winn LLC and its sister company, Wilary Winn Risk Management LLC, provide independent, objective, fee-based advice to over 600 financial institutions located across the country. We provide services for CECL, ALM, Mergers & Acquisitions, Valuation of Loan Servicing and more.

Released November 2025

Introduction

The post-pandemic, inverted yield curve environment has challenged credit unions of all sizes to carefully manage their balance sheets, interest rate risk (IRR), and capital. This paper examines asset liability management (ALM) strategies utilized by credit unions on either side of the $500 million asset threshold, and how smaller institutions can safely adopt the approaches of larger complex peers as they grow, in order to effectively manage IRR, improve earnings, and protect capital. The focus is on data-driven insights and industry analysis in the post-pandemic period, where short-term rates have exceeded long-term rates.

Duration In ALM

Before examining the various ALM strategies that have been deployed in recent times, it’s important to define duration and how it affects an institution’s interest rate risk. While there are multiple variations of duration, this paper will refer to effective duration. Effective duration measures the price sensitivity to interest rate changes, considering potential changes in cash flows due to options such as call or put provisions. Assets with longer durations (like a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage) will respond more to changes in interest rates, which makes them more beneficial as rates decrease and less beneficial as rates increase. The opposite is true for the liability side of the balance sheet. Ultimately, IRR arises when there is a mismatch between the duration of assets and liabilities. A more in-depth explanation of duration can be found in our white paper, Understanding Duration Analysis: A Concept for Asset Liability Management.

Non-Complex Credit Unions

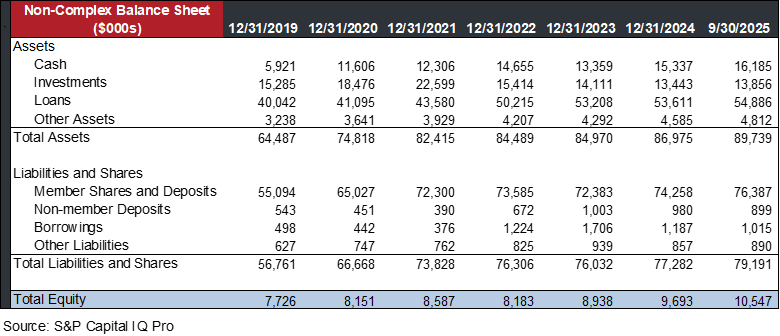

The following table shows the historical average balance sheet for non-complex credit unions from 2019 through the third quarter of 2025.

As shown in the previous table, the smaller non-complex credit unions tend to operate with more conservative balance sheets than their larger counterparts. This takes the form of maintaining higher liquidity and less aggressive loan deployment. Ultimately, this means that non-complex credit unions tend to hold a greater proportion of shorter-duration assets. Following the surge in deposits at the early stages of the pandemic, many credit unions were flush with cash while loan opportunities slowed. In the years following, lending opportunities rebounded significantly, but the non-complex credit unions maintained those higher levels of cash due to the rising cash yields coupled with concerns about having liquidity to meet member needs. The following table shows the historical asset concentrations for the non-complex credit union group.

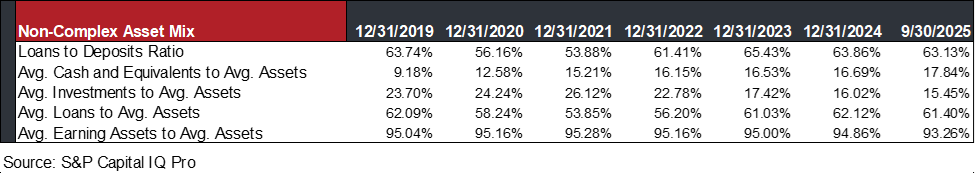

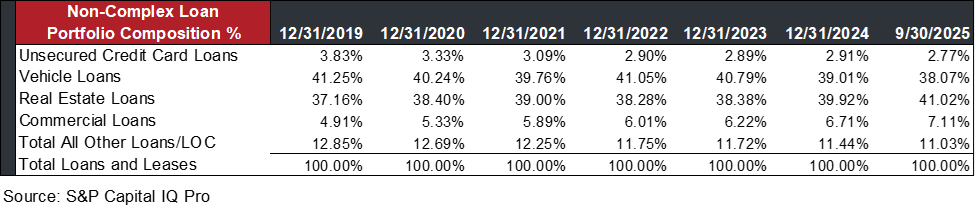

As previously stated, following the surge of deposits in the COVID environment, non-complex credit unions have increased their cash concentration, allowed investment portfolios to run off, and slowly increased their loan portfolios. To manage IRR, non-complex credit unions have balanced the increased cash position along with shorter-duration and adjustable-rate lending. By keeping asset durations shorter or rates adjustable, these institutions naturally limit their interest rate risk. While they typically do not engage in complex derivatives, techniques like capping loan maturities or maintaining higher liquid reserves generally limit risk. The following shows the historical concentrations of the non-complex credit union’s loan portfolio.

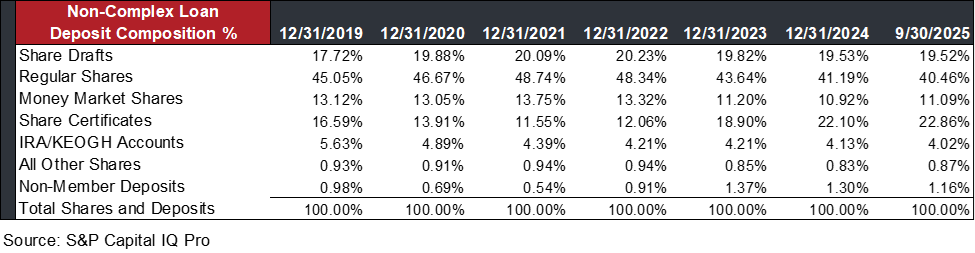

On the liability side, non-complex credit unions tend to rely on traditional member deposit products from the local communities that they serve. The concentrations of these deposits are shown in the following table. We note that the focus on core deposits helped maintain a notable concentration in regular shares even as rates began to rise in 2022. These deposits are less responsive to rising interest rates, which helped protect earnings. However, similar to that of the industry across the board, non-complex credit unions have increased reliance on more expensive share certificates. This IRR was largely managed by certificates being promotional shorter-term offerings, on which durations tended to be shorter and match the asset side of the balance sheet.

In conclusion, non-complex credit unions, while having fewer ALM techniques than that of their larger counterparts, have a few inherent ways of limiting IRR. Limiting asset duration by maintaining proper liquidity levels coupled with shorter-term consumer lending and offering adjustable-rate products can largely lead to a stable profile when paired with a strong non-maturity deposit base and duration matched share certificates.

Complex Credit Unions

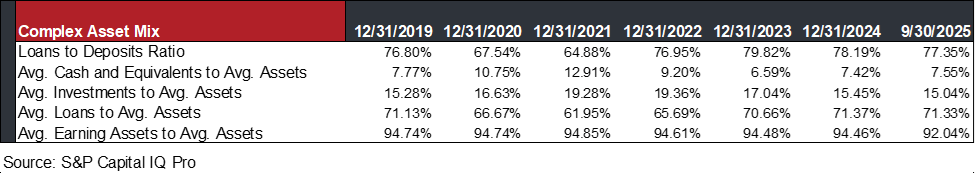

The following table shows the historical average balance sheet for complex credit unions from 2019 through the third quarter of 2025.

Credit unions above $500 million in assets are considered complex by NCUA standards, and they tend to employ more sophisticated and aggressive balance sheet strategies. These institutions account for the bulk of the industry’s assets and growth. This is shown above as the average size of the complex group has increased significantly in the period shown. With greater resources and scale, large credit unions can utilize advanced techniques to manage interest rate risk and capital and diversify their funding beyond core deposits. This allows the complex credit unions to have significantly higher loan- to-share ratios, with several sizeable institutions sitting above 100%. We note that the historical asset mix for the complex group is shown in the following table.

The preceding table illustrates the stark contrast to smaller institutions that often have more idle liquidity. Complex credit unions achieve such high utilization rates by aggressively growing loans like auto lending, mortgages, credit cards, member business loans, and new personal loan products by supplementing the deposit base with external funding when needed. It’s not uncommon for a complex credit union to use borrowed funds or wholesale deposits to support loan growth beyond what member deposits alone can fund. For example, many larger credit unions are members of the Federal Home Loan Bank and have borrowing lines with a corporate credit union listed as vital sources of cash in liquidity crisis plans.

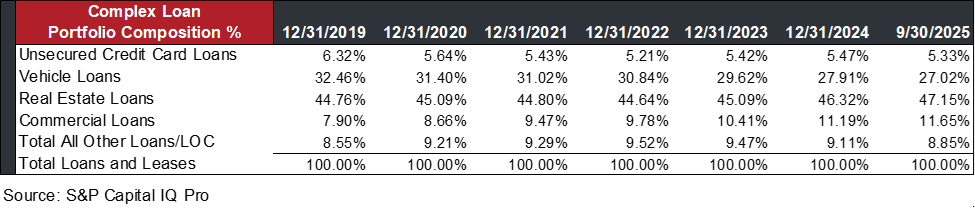

The loan mix at large credit unions is also more diversified, as shown in the following table. Whereas a non-complex credit union might stick mostly to consumer loans, a complex credit union often has significant long-term real estate loans, commercial loans, participation loans, student loans, and other higher-yield or longer-term assets. These assets can boost yield but also carry more interest rate and credit risk.

Complex credit unions employ sophisticated ALM practices and a wider array of IRR mitigation tools. Complex credit unions conduct regular earnings at risk (EAR) and economic value of equity (EVE) simulations using sophisticated ALM models. ALCOs of these complex credit unions meet regularly to adjust strategies to manage IRR through tools such as deposit/loan pricing/volume, derivatives, and usage of secondary capital.

Complex credit unions have broader charters and large marketing budgets, which allow them to pursue deposit growth on a regional or even national scale. Many larger credit unions have open or multi-segmented fields of membership, allowing them to serve expansive geographies. For deposit gathering, complex credit unions can offer very attractive rates on select products when needed. For instance, some have rolled out high-yield money market or online-only savings accounts to draw funds from outside their core member base. Other large complex credit unions that can absorb short-term margin pressures run high-yielding short-term certificate specials to quickly raise liquidity with the key ability to turn the specials on or off as needed. Additionally, complex credit unions have increasingly attracted commercial accounts and other large depositors. By attracting local businesses, non-profits, and municipal accounts, a credit union can gather substantial balances that allow for more lending. For example, offering specialized business checking with moderate dividend rates helps bring in relatively stable operating balances from organizations. Larger credit unions have the sophisticated treasury management services needed to serve these clients, which may be something many small credit unions lack. These business deposits diversify funding and tend to be less rate sensitive. In summation, complex credit unions deploy a strategic mix of funding consisting of core member deposits as the foundation, but they augment with brokered deposits and borrowings to achieve an optimal cost of funds and support strong loan growth. They actively manage their liability mix as another lever in ALM to change the duration profile of the institution. A complex credit union might decide to extend the duration of its liabilities by offering a special 5-year CD, or conversely, use floating-rate FHLB advances to fund fixed loans or vice-versa.

As previously stated, on the asset side, complex credit unions have more diverse loan portfolios with a mix of product types with both short and long durations, which allows the credit union to naturally hedge against swings in interest rates. In addition to loan mix, the NCUA has given complex credit unions greater latitude to use derivatives for hedging. This means a complex federal credit union can enter interest rate swaps, caps, swaptions, and other derivative contracts to hedge IRR, provided they have been approved to do so or if they have a CAMEL rating of 1 or 2. Many complex credit unions can now routinely utilize interest rate swaps to convert fixed-rate loan exposure to variable, or interest rate caps/floors to protect net interest margin during rate swings. For example, a credit union heavily concentrated in fixed-rate mortgages might buy interest rate caps or enter swaption agreements to offset the convexity and duration risk on those loans. These instruments help larger institutions manage an inverted yield curve by limiting the downside of rising funding costs against fixed loan yields.

For capital management, credit unions crossing $500 million in assets must either comply with Risk-Based Capital (RBC) requirements or opt into the Complex Credit Union Leverage Ratio (CCULR). While RBC assigns risk weights to asset types and requires a 10% RBC ratio for a “well capitalized” status, CCULR, on the other hand, allows qualifying credit unions to bypass the granular RBC calculations if they maintain a simple 9% net worth ratio along with certain constraints on off-balance-sheet exposures. Complex credit unions thus target capital levels that support their risk appetite and growth plans. Many manage to an optimal net worth range that is high enough to be comfortably above regulatory minimums, but not so high as to unduly restrain growth or returns. For complex credit unions subject to RBC, they must hold extra capital for concentrations in areas like long-term mortgages, member business loans, or investments with high-interest-rate risk, which has led some credit unions to limit exposure to certain assets. For complex credit unions subject to CCULR, simply maintaining a higher net worth ratio typically covers risk in aggregate. In summary, complex credit unions have more flexibility to raise and allocate capital either through managing existing assets, potentially merging in a smaller credit union, or issuing subordinated debt.

Following NCUA rule changes, any complex credit union can issue subordinated debt to investors, counting it as Tier 2 capital for RBC. By issuing subordinated debt, complex credit unions effectively borrow capital to fuel faster growth or strategic expansions. The trade-off is paying high-interest rates to investors, which can notably impact earnings. However, in return, the credit union gains immediate capital that can support expanding the balance sheet and hopefully generate higher future income. Many of the biggest credit unions have used subordinated debt to fund aggressive membership growth, bank acquisitions, new branches, and technology investments without diluting their net worth ratios below well capitalized levels. For instance, a credit union might issue $50 million in sub-debt and use those funds to originate $500 million in additional loans over time; provided that the ROI on those loans exceeds the cost of the debt, the strategy pays off. It also bolsters the credit union’s ability to absorb interest rate shocks or credit losses with less risk to member capital. Ultimately, complex credit unions must also consider capital management, within the framework of their ALM profiles.

How Non-Complex Credit Unions Can Safely Adopt These Strategies

As a sub-$500 million credit union grows, it can benefit from the playbook of larger institutions but must do so prudently to avoid undue risk. Here we outline how smaller credit unions can safely implement big-credit-union strategies in areas like lending, funding, IRR management, and capital planning, especially as they approach the $500 million threshold and look beyond.

A growing credit union should gradually enhance its ALM capabilities. This means investing in better analytical tools or external ALM services to simulate interest rate scenarios and measure IRR. Before venturing into long-term assets or complex instruments, ensure the board and management understand the risks and have policies in place to limit exposure. For example, if a $300 million credit union wants to start holding 30-year fixed mortgages, it could first establish concentration limits (e.g., no more than 20% of net worth) and possibly use simple hedges like selling loan participations or lengthening some liabilities. As a credit union grows, those policies should evolve to become more granular and robust, similar to a complex credit union’s policy. By building ALM sophistication step by step, a growing credit union can safely improve its IRR profile with better risk monitoring.

A growing credit union should look to diversify funding sources. Small credit unions can enact this by establishing contingent liquidity early. For example, management should consider joining the Federal Home Loan Bank well in advance of needing major borrowings. Even if an advance isn’t needed today, having membership and borrowing capacity ready adds safety. While day-to-day operations might still be funded fully by member shares, having these levers in place allows a growing credit union to confidently pursue higher loan-to-share levels that would boost earnings. For instance, if a small credit union plans to ramp its loan-to-share ratio from 70% toward 85%, it should consider having an FHLB line of credit or a pool of excess liquidity investments that can be sold, so that any deposit outflows or rapid loan growth can be readily covered. Additionally, competing with larger institutions may require adopting some of their tactics in a calibrated way. A smaller credit union could introduce a high-yield checking or savings product to attract and retain members, much like large credit unions, but structure it with potential balance caps or requirements to control costs. Additionally, as it grows, a credit union can expand its field of membership or digital outreach to broaden its deposit base like complex credit unions have. This might involve converting from a single-sponsor charter to a community charter or joining shared branching networks to increase convenience. By widening the membership pool and offering additional deposit products, the credit union gains more leeway to gather deposits from more sources, both consumer and commercial.

A growing credit union should safely expand the loan portfolio. On the asset side, as a credit union grows, it is most often through increased loan originations. As previously mentioned, most complex credit unions have more diverse loan portfolios that help offset IRR. As increased lending opportunities arise, new loan products should be brought onto the balance sheet in a controlled manner. If a $400 million credit union has never originated commercial or indirect auto loans but sees the opportunity to do so, it should first invest in expertise before booking large balances. A smaller credit union should establish prudent internal limits and grow these portfolios in proportion to capital. By the time the credit union crosses $500 million, it will have a balanced loan mix with established performance history, much like larger peers, but without having taken undue interest rate and credit risk. Additionally, selling loan participations can be a valuable strategy to emulate complex credit union balance sheet optimization. Complex credit unions routinely buy/sell participation loans to manage concentration and liquidity. A growing credit union can sell portions of its new loans to remain within risk limits and free up capital.

A growing credit union should prepare for changing capital requirements. Perhaps the most critical difference as a credit union grows is the approach to capital. A small credit union should start planning early for the $500 million threshold where RBC or CCULR is required. Well before that point, management should understand how their capital ratio would look under the RBC rules. If the credit union expects to opt for CCULR, it should aim to build its net worth towards 9% by the time of crossing $500 million. If RBC is chosen or required, the credit union might need to adjust its balance sheet concentrations. Thus, prudent capital management as a credit union grows might mean temporarily throttling asset growth to boost the net worth ratio, or diversifying assets to lower the overall risk density. Additionally, growing credit unions can consider issuing subordinated debt once eligible, but should do so carefully. A smaller credit union should likely start with a modest issuance if it decides to raise subordinated debt and possibly target impact investors or programs that offer favorable terms. The credit union should project the effect on earnings and net worth, especially within the context of changing interest rates.

Conclusion

In conclusion, non-complex and complex credit unions employ distinctly different strategies appropriate to their scale from how they structure their balance sheets and manage interest rate risk, to how they gather deposits and bolster capital. Smaller credit unions prioritize liquidity, simplicity, and high capital buffers, whereas larger ones maximize asset deployment, use sophisticated IRR tools, and tap external capital markets. We note that the current inverted yield curve environment and recent rate cuts have made thorough ALM practices all the more critical when running an institution. There is much that smaller institutions can learn and adopt from their complex peers’ operations. By carefully phasing in these strategies and upholding sound risk management, growing credit unions can enhance their competitiveness and member service without compromising safety and soundness. The result is a continuum of best practices that can help all credit unions thrive, each according to their size and mission, even in a volatile rate landscape.